Smarter and Smaller Houses, an Introduction to Design

Last year, Merriam-Webster voted “austerity” the apparently coveted status of Word of the Year. The negativity around the term can be seen in the riots of Greece and Spain and Great Britain. The word “austere” includes definitions such as “stern and cold in appearance”, “markedly simple or unadorned”, and “giving little or no scope for pleasure”. No word better captures how many people would react if I were to suggest the concept of building small, particularly at a time when more is perceived as better. And no word could be more misleading and wrong to the great potential of this “other” design approach. So, to establish a new frame of reference, let me throw some new words into the pot for consideration;

Efficient

Effective

Essential

Economical

Connected

Comfortable

Convenient

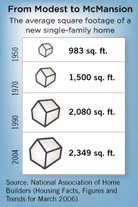

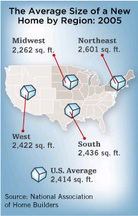

In only sixty years, we have witnessed an interesting phenomenon in the United States. The average size of a family has seen a 30% decrease, from 3.6 to 2.7 or one person. Over the same period, the average house increased by 140%, from 1,000 to 2,400 square feet. I’ll let you make any connections between life then versus now, as that is another conversation altogether and getting preachy here detracts and distracts from the power of a very powerful design methodology.

Put simply, when built using the same conventional methods, small houses cost less to build, operate, and maintain. It seems obvious, but building less means a directly proportional reduction in the materials and time required to build, and in many cases the actual per-piece costs for materials is reduced as well. Operationally, costs are reduced by limiting the resources needed to make the house work and be comfortable to live in. And from a maintenance perspective, less time and money is put into cleaning, repairing, and eventually replacing all the components that go into a house. When capitalizing on the full capabilities of new technologies and the better understanding of traditional ones, these savings are compounded. And by corollary, for the same cost, if you reduce the square footage, you can increase the cost per square foot, meaning a smaller house provides an opportunity for higher quality or more features.

This is a topic that has been covered by smarter people than I, and in greater detail than I’ll get into. I intend only to provide an overview, emphasize a few simple points, and show some commonly pursued tactics as well as some uniquely innovative ones. Most importantly I hope to reveal the underlying philosophy that supports it all, to shed light on the “other” design approach I mentioned at the top.

Architecture specifically is commonly perceived as an answer to some problem, a solution, a thing. The emphasis is on the result. However, architecture specifically and design in general, has been more accurately defined as “problem solving” or “problem seeking”. Design as process, not product. In order to solve a “problem”, it is critical to first understand it, to ask questions in order to discover its essence in as much detail as possible. So, when it comes to designing a small house, let’s focus on the questions being asked as a means to understand the answers that result;

What do you want in a home?

What do you need in a home?

What limitations are there?

What opportunities are there?

I would invite you to go through a sort of design process with me moving forward, answering these questions as best you can. Consider the design of your dream home, your vacation home, or just reimagine your current home. Consider the addition or renovation you’ve been contemplating.

Designing a small home, as it should be with any home or any building, is really nothing more than being smart about it, balancing what you need with what you want with what you have. Designing small, is designing smart.

Stay tuned for more installments on this topic in the coming weeks. Derek can be reached via email to discuss a specific project.