As I get ready to do something I’ve never done before (to “blog”), I’ve been pondering what exactly I will be talking about. Let’s face it, blogging is just editorializing, talking about stuff that could be anything from pure opinion to well researched short topics. It’s conversational, topical, ideally informative, and preferably entertaining. One topic continues to rise to the top as an item of critical importance to those of us in the design service profession; the client.

Clients are critical, for without them we literally have nothing to do. Even if we’re designing our own dream homes, some theoretical super “green” high rise, or even a floating city as a movie set, there is a client involved. This client may be imaginary, but there is still a list of wants, needs, and limitations that make up the foundation of the problem that any project proposes to solve. Design professionals are in the end, just problem solvers, so no problem, no solution.

What I’ve come to really appreciate about great architecture, and all its design cousins, is that the resulting physical thing (the answer), while attractive and meaningful, is servant to the problem statement, the question being asked. This question is the foundation of the project, and it lives in the mind of the client, although it is the job of the design professional is to help discover it truly and describe it thoroughly. This is a collaborative process where the design professional is critical, but where a forthright, cooperative, patient, and trusting client is invaluable. Without the client fully embracing their role, their responsibility in this partnership, the designer is limited to making it up and mailing it in.

As I want to salute and define what it means to be a great client, let’s assume a talented, experienced, and thoughtful design professional is on board. I’ll talk about design process in the future, defining what the differences are between bad, average, and great design professionals.

A great client is an active partner in a process of problem discovery, willing to accept that the initial problem statement may be partially or even completely wrong. “I need a two storey addition on my house because I need a master suite and new kitchen, and it should be built on the back right here.” It’s a great place to start, a very necessary step, but what should happen next is a lengthy and thoughtful process of understanding what is and what needs to be, as well as what limitations and opportunities exist that will impact the project. Afterwards, we may learn that an addition wasn’t necessary at all in order to accomplish a renovated kitchen and a basement master suite.

As we all know, time is money, and thinking takes time. Particular in tough economic times (now), with tight budgets (usually), or with challenging schedules (often) this phase is often truncated or eliminated in order to expedite the next phase (design and documentation). While understandable on the surface, does it make sense to rush into battle without some understanding of your enemy, the field, the weaponry available on both sides, and then of course the role of this battle in the bigger war? It is critical to think before leaping, and that takes time. To inadequately plan is to just roar your battle cry and go charging down the hill and hope for the best. Almost any professional will keep a client out of harm’s way, giving you something safe and functional, something adequate. But such thinking does not make for great projects.

A great client also trusts the design professional and the discovery process. If there is no trust, the whole design process is irrevocably broken and the result will be mediocre at best. Trust does not mean being led by the nose or letting the professional have their way. It means allowing the process to work, for questions and answers to flow, and then questioning answers, even when they seem obvious. Depending on the complexity of the project, there could be numerous formal rounds of this, although truly the questions never cease to come until the project is built.

Lastly, a great client is a thinking client, one that challenges their design professional and is willing, even asking, to be challenged themselves. For the process to work best, all parties involved need to be offering up their best, while insisting that their partners are doing the same. You would be surprised how opportunities are uncovered and obstacles are hurdled by honest and thorough collaborative deliberation.

So, what makes for a great client? Time and Patience. Trust. Thoughtfulness.

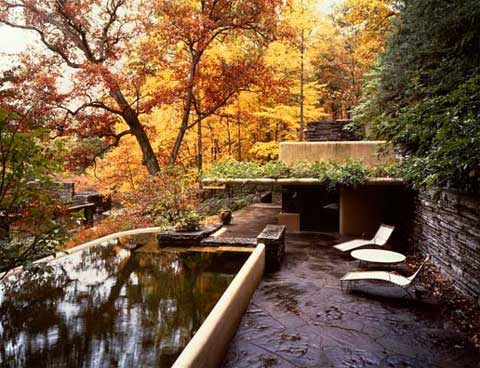

Done properly, this process results in projects exceeding expectations. You’ll see I’ve included images of Frank Lloyd Wright’s Fallingwater. This is the first time I remember learning of a project achieving such awe inspiring timelessness because a client offered an inconceivable amount of patience and trust to the architect. The client wanted a vacation home that celebrated their family’s favorite swimming and picnicking spot, and trusted Mr. Wright to give it to them while they vacationed abroad. What they got was totally unexpected and completely restated the original problem statement. Their house was built over, on, and around their favorite spot. Their house became their favorite spot.

To read more of the history of Fallingwater, please visit the website.

Please contact Derek via email for more info or questions about a specific project.

Excellent article, a very enjoyable read. I am also a fan of Fallingwater as an example of something beautiful and well integrated.

Often it is the most trusting client that gets the best value out of the project, since all the $ end up in the finished project rather than a million revisions. As long as their desires and ideas are clear at the start it works out well.